I’m Lovin’ It: The McDonald’s India story

Editor’s note: Localised menus, spicy aloo tikkis, desi-fied burgers with masala and chutney, Happy Meals and toys, throwaway prices in prime locations, breakfast sandwiches and mid-day coffees. Akhil Sood writes about the history of McDonald’s—that shining beacon of American consumerism—and how the chain has, over three decades, won over the Indian market through clever adjustments, localised adaptation, and timely pivots.

Written by: Akhil Sood

*****

A wave of familiarity washed over me as I burnt my tongue at a McDonald's in Singapore. After a night on the town, I found myself with the munchies in the dead hours. I walked into one of the few available options, a 24-hour McDonald’s, and ordered the apple pie.

McDonald’s India used to serve this apple pie around 20-odd years ago. Chunks of apple melted into a lava-like consistency, ensconced in a crisp, crackling crust. A baked apple pocket or turnover rather than a pie really, similar in appearance and shape to the Pizza McPuff. It was served at blisteringly high temperatures—it was meant to be eaten piping hot—and I, being a child, did not yet possess the virtue of patience. Every time I ate it, it would burn my tongue. All these years, I assumed it had been discontinued by McDonald’s, period. Turns out, the pie has been thriving in other parts of the world. We are among the deprived, deliberately so, to conquer the Indian fast food market.

It had an 11% market share in terms of revenue in the Quick Service Restaurant (QSR) sector in 2023, with a revenue upwards of $22 billion. Through aggressive marketing, a menu infiltrated by desi flavours alongside traditional American offerings, at venues that attract Indians from across the social spectrum, in big cities and smaller towns alike. Over the past three decades, McDonald’s has carved an important space for itself in fast food in India.

Take, for example, the McDonald’s outlets at Connaught Place in New Delhi. Bang in the centre of the city and easily accessible, CP is not cordoned off from the less privileged unlike, say, a Khan Market or the upmarket malls.

Inside you’ll likely spot cash-rich millennials seeking a quick bite, parents with kids on a family outing, children’s parties, couples on dates, professionals at lunch meetings, college students being loud and brash, people of all classes and backgrounds speaking a dozen different languages. There’s a vitality to any McDonald’s you visit in India, fuelled by Mcaloo Tikkis and Happy Meals.

Seasoned critics and amateurs alike have routinely described McDonald’s as tasting like “cardboard”. It’s ultra-processed and starchy, painfully unhealthy in ways I’d rather not learn about. And yet it persists in the Indian imagination. This—as evidence and experience both suggest—has been made possible thanks to an ability to change and respond to the Indian palate in its early years, making accommodations for an extremely price-conscious audience. They followed this up with timely pivots to adapt to market dynamics as the country’s habits evolved. Through familiarity and novelty both, through innovation and adaptation, today McDonald’s—with over 500 outlets in India, per a 2025 report—is practically an Indian institution.

---

After my late-night apple pie, I also got myself something called an apple custard pie. (As anyone with a raging sweet tooth would attest, a snack actually means “two snacks minimum” when it comes to dessert.) The apple custard pie was a limited-edition thing there; it was roughly the same as the regular type, but it had an additional layer of gentle custard to contrast against the fiery tendencies of the molten lava—a smooth line running through the dish. Incredible.

This cascade of revolving dishes across outlets is just something they do. Everywhere. I had previously assumed that the desi-fication of McDonald’s was a business decision made to cater to a market as humongous as India, with its unique flavour profile. But as it turns out, the McAloo Tikkis or the McSpicy Paneers and the Maharaja Macs, items I’d dismissed in my head as little more than naked big business opportunism, are part of a broader global strategy. They develop dishes based on local taste profiles and cultures for their region-specific specialty menus.

In Thailand, for instance, I had a taro pie, another steaming hot turnover pastry with bright purple goo inside, made using taro, a root vegetable found in the region. The Philippines has a McSpaghetti, based on a popular fast food dish in the country. In parts of Europe, they serve local beer at the outlets. Spain had a square burger called the McIberica, with Spanish ingredients. Even the French, fussy little basta… particular about their food that they are, have embraced McDonald’s courtesy the McBaguette (naturally).

The taro pie in question.

This article in Far Out magazine, in fact, coined the term ‘Big Mac Tourism’ (partly, if not entirely, tongue-in-cheek), to describe the diverse local McDonald’s cuisines across the world that travellers seeking comfort might find. The Teriyaki burger in Japan, the Bulgogi in South Korea, the McArabia in Saudi Arabia. And on and on. In India, too, I remember some dosa burger and all manner of culinary disasters that they fumbled around with in the mid-2010s.

Photojournalist Gary He has a book about this, called McAtlas. A 2025 article in the BBC details some of his global adventures for the book. “While many believe McDonald's has homogenised food culture worldwide, He argues the opposite: that the company has thrived by adapting its menu, architecture and brand to local palates and traditions.” In his own words:

"McDonald's has succeeded because they have brilliantly incorporated local flavours and ingredients – from the McRaclette in Switzerland to egg bulgogi burgers in South Korea and the Halloumi McMuffin in Jordan," He says. “Without adjusting, without localising, without kow-towing to local tastes and local cultures, you can't do business on an international level, no matter how big or powerful you are.”

Taupo, New Zealand

Taupo, New Zealand

Recently, a clip resurfaced in the news—well, social media—featuring an Indian woman at a McDonald’s outlet somewhere in southeast Asia. She’s screaming her lungs off at an employee for serving her a burger with meat in it. She’s vegetarian, and it goes against her religious sentiments.

I don’t know the entire story (which has sparked off a tedious culture war over at X about, what else, vegetarianism), but it made me think: McDonald’s in India is basically its own thing, with little connection to the wider McDonald’s universe beyond our borders. We never even got the cheeseburger here, nor did we get the hamburger or Big Mac, all of them made with beef. In fact, India was the first country where McDonald’s went beefless, without any of its flagship burgers. Is McDonald’s, at least the way we see it, part of our culinary identity now?

---

The chain opened its doors here in 1996, via an outlet in Delhi’s Basant Lok market to much fanfare. Days later, a second outlet in Bandra. The shining epitome of American consumerism was upon us, finally. At the time, the launch of a global iconic brand was a landmark event in the trajectory of a liberalising India. The long, winding queues you see outside the Sex and the City-famous Magnolia Bakery in Gurgaon were de rigeur in the early days if you wanted a bite of the McChicken or the McVeggie burgers they started off with.

While not exactly premium (a McChicken cost between Rs. 35-45), McDonald’s was at its outset upmarket fare, reserved largely for the anglophone, upper-middle classes. It also carried a certain cachet that brands like Wimpy, local chains such as Nirula’s, or the standalone Kent’s didn’t possess. We also had burgers at regular desi restaurants: a fat aloo, chicken or mutton patty topped with coleslaw/stringy lettuce, chunky tomatoes, and a slice of Amul cheese.

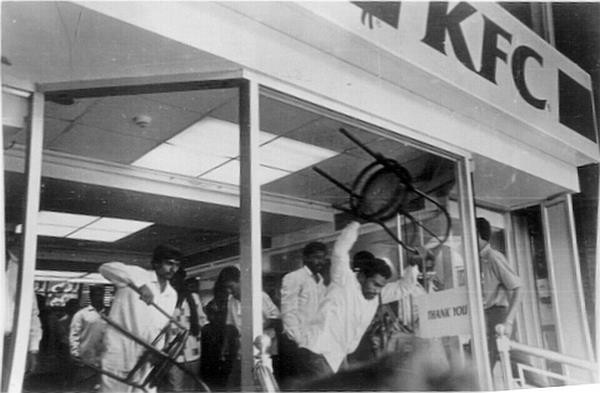

McDonald’s was not the first global fast food chain to set up shop in India. That (dis)honour belongs to KFC, which opened in June 1995, and promptly fell victim to anti-liberalisation fervor. Protesters chanted ‘death to KFC’ as they ransacked outlets across the country. While their wild accusations ranged from overuse of MSG to arsenic-fed chickens, the real fear was that KFC would destroy the business of local restaurant owners (much as fast-ecommerce is today considered a threat to kirana stores). Fears that have since been proved groundless. Thirty years after McDonald’s’ entry into India, local burgers have continued to thrive and mutate—like this Lucknow street version served with fruit buns, no less.

Protesters vandalising the original KFC outlet in Bengaluru in 1995.

---

In the early years, McDonald’s was a niche brand. Even though the Indian outlet was the first in the world to shun beef and did its best to woo vegetarians, most Indians remained unimpressed with its all-American fare:

"I think they have to work on the taste," said Ajit Suri, 41 years old, after biting into a Vegetable McNugget. Vandana Gupta, a personnel recruiter, approved of her mutton McBurger but her 29-year-old brother, Rohit, was underwhelmed by his McChicken. "We don't like bland food," he said.

Within a year of doing business, the brand’s local partners like Vikram Bakshi realised “we have to change if we have to survive.” Soon McDonald’s launched what would become its true big-ticket item: the McAloo Tikki, a compact burger with a spicy potato patty and a distinct desi essence.The ‘innovation’ was amusingly close to the version served at the local restaurant, with one crucial difference. What we had were potato patty burgers that were an Indian attempt to make an American burger. It’s a fine distinction, but the McAloo Tikki was instead an American attempt at making an ‘Indian burger’.

Unapologetically, It had tangy chutney, not sauce; onions rather than lettuce; chatpata masala, not sanitised seasoning. During an era where foreign fast food chains still remained a relative oddity, and McDonald’s had the cachet mentioned above, there was a charm—and a cultural collision—to the experience of eating this dish at a buzzing restaurant space designed much like international fast food chains.

In time, they’d go on to launch the chicken cousin of McAloo Tikki, called the Chicken McGrill (which was, after an influencer-driven campaign, brought back to menus in 2020). The McGrill had a thin, masala-heavy chicken patty along with a mint chutney instead of the mayo-adjacent white sauce. Even so, the McAloo remains the most popular item on the McDonald’s menu, followed by McVeggie and McChicken.

The success of McDonald’s lured KFC back in 1999. It now competes with McDonald’s and Domino’s for primacy among fast food chains, though it has faced challenges in overcoming its singlemost disadvantage relative to its two biggest rivals. Indians were familiar with pizzas and burgers before either McDonald’s or Domino’s set up shop. But the idea of buying a giant bucket of fried chicken was completely new. In one sense, KFC’s success in integrating an unfamiliar dish into the Indian palate is far more impressive than McAloo Tikki’s success.

---

While McDonald’s may have needed to adjust its menu for taste, it came pre-tailored for the Indian market in two important aspects. The first was a freakishly low price for a foreign brand burger. If memory serves, a McAloo Tikki burger when it first launched cost a mere Rs 12. Domino’s, on the other hand, priced its pizzas between $2-$10 (up to Rs 350 at the 1996 exchange rate). McDonald’s was also family-friendly, an appeal that has been core to its brand since its inception in America. Every outlet had a bench outside with its much loved clown, Ronald McDonald. Happy Meals with toys included were specifically aimed at children. The outlets were tailored to be perfect venues for birthday parties, with a special high chair for the birthday boy/girl.

These factors all contributed to its rise in the late ’90s and the 2000s. It had an unchecked run for a decade or so, winning the American fast food wars here comfortably. Domino’s, Pizza Hut, and KFC were the prime contenders, but McDonald’s remained the king. In 2008, however, the McDonald’s express train hit a snag. The company got into a lengthy and ugly legal battle with Vikram Bakshi when it attempted to buy him out, threatening vendors who supplied outlets owned by him. The fallout was a bizarre shape-shifting menu and a strange, desolate, end-of-world feel at McDonald’s outlets

The Wall Street Journal reported at the time:

Menu items have started disappearing. First to go were the McFlurry desserts and other items that use soft serve. Last Friday, the popular Maharaja Mac—an Indian version of the Big Mac in which the beef has been replaced by either chicken or cheese-and-corn patties—and McSpicy chicken dropped off the menu at a restaurant in New Delhi’s popular shopping district Connaught Place. “Sold out” signs were pasted across menu boards. The sandwiches were back on Saturday, but restaurants in New Delhi said they were still missing jalapeños, tomatoes, milk and Pizza McPuffs. Meanwhile, some outlets seemed to have run out of some sizes of McDonald’s cups.

The legal feud was finally settled following a buyout in 2019, but by then McDonald’s had a new set of problems to solve.

---

For the first decade and a half, McDonald’s could afford to coast on novelty, price, and brand value. In the 2010s, however, consumer behaviour was starting to shift. KFC was on the rise, Burger King entered India, and Starbucks and Dunkin’ Donuts offered a novel cafe experience—all eager to woo a more aware consumer with growing incomes and greater choices. The solution, as Scroll noted in 2017, was to pivot upwards:

As a result, in 2013, Westlife decided to change tack, investing in revamped restaurants, new upholstery, and lighting, besides an expanded menu with prices and flavours designed to appeal to younger consumers. In 2015, it also relaunched the fast-food chain’s most expensive burger in India, the Maharaja Mac, priced between Rs 176 and Rs 194. Over the past few years, the company has been spending more marketing money on pricier burgers and new flavours.

The company also launched McCafes in 2013, offering cheaper coffee than Starbucks, along with muffins, and cookies. Localisation was taken to a whole new level. Example: a masala dosa-inspired burger that it began experimenting with in those years. By 2022, McDonald’s had added Masala Dosa Brioche, Anda Bhurji, and Chatpata-Naan, and Italian and Mexican rice bowls. Of course, fusion cuisine at local joints has since moved way past tikki burgers—onto far more exotic items like momo or paneer tikka pizzas and butter chicken tacos.

---

The fast food or the Quick Service Restaurant (QSR) industry is expanding at a heady pace. Devyani International and Sapphire Foods India, which operate KFC and Pizza Hut, respectively, in India have merged. Foreign and Indian investors are pouring money into Subway, Wow Momo and even Haldiram’s—which plans to expand into Western fast food, bringing in the American sandwich chain Jimmy John's. Mcdonald’s franchise owner (in South and West India) Westlife is still a major player, but it can no longer rely on the golden arches or just localisation to retain its customers. But after TK years in India, the grandpa of fast food brands has one market advantage: habit. I now go to McDonald’s not for the taste, but for items on its menu that I’ve eaten for most of my life. In the world of fast food, it’s the no-brainer choice: familiar, predictable, with a casual, low-stakes energy. And, good or bad, even today, each outlet remains packed.

*****

Akhil Sood is the editor at Advisory.

souk picks

souk picks