David Foster Wallace: A reading list

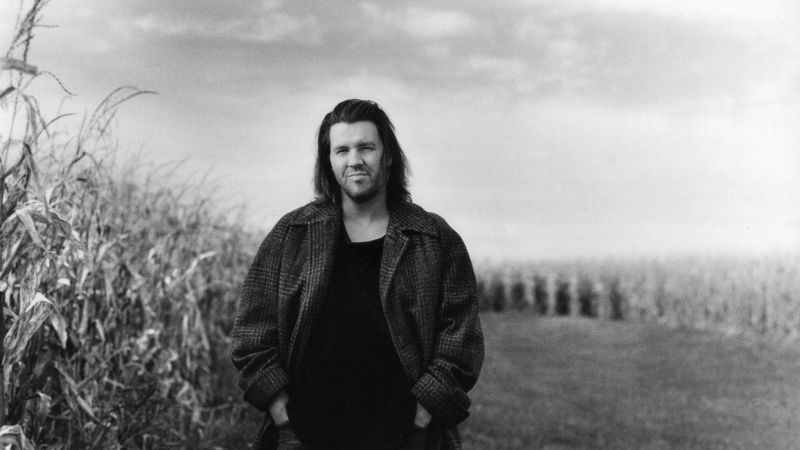

Editor’s note: American author and essayist David Foster Wallace, best known for his sprawling comic masterpiece Infinite Jest (1996), divides opinion sharply. His work, while widely respected and revered among a die-hard legion of fans and critics, has also come under fire for being symbolic of a ‘literary-bro’ archetype. As the book turns 30 this year, Advisory Editor Akhil Sood takes us on a deep dive into the writer’s canon of tragic, complex, maximalist, hilarious, insightful, and densely packed work. Here’s a reading list for anyone curious about this gifted but flawed author.

Written by: Akhil Sood

*****

FICTION

Infinite Jest (1996)

A maximalist pomo fever dream—devastating satire of America; hilarious character study; searing tragicomedy. Infinite Jest is arguably one of the most electrifying novels of the past 50 years. The dysfunctional Incandenza family lies at the heart of an expansive and impenetrable plot that shuffles across locations and timelines, with hundreds of characters and zigzagging plotlines. It’s obsessive and frantic. Wheelchair assassins fronting a separatist movement, tennis academies, deformed characters, drug addicts, incestuous affairs—and a MacGuffin-esque film called “Infinite Jest”; whoever watches it reaches a state of euphoria that leads to their death.

This is also a novel mired in infamy and ‘discourse’, dismissed as a hipster appendage, or a kind of lit-bro almanac. Ignore the noise because, while gruelling in terms of length and what it asks of its readers, the pages are bursting with life and heart, and it remains outrageously funny.

NB: It clocks in at 1,079 pages, of which around 100 are dedicated entirely to geeky, elliptical endnotes. Keep two bookmarks handy. As well as a dictionary; maybe a medical dictionary too. And an energy drink. The writing is long-winded and stylistically showy, be warned, but there’s usually an emotional payoff attached to the aesthetic chaos of Wallace’s prose.

‘Good Old Neon’ (Oblivion, 2004)

An ad exec in his 20s, in this largely first-person short story, is confronting his feelings, via a conversation with a psychoanalyst, about who he is. He is talking about how he’s been a fraud his entire life, doing things only to appear a certain way to the world. He is consumed by imposter syndrome. He reveals that he has killed himself. And we hear the events and emotions that led up to this tragedy. The story was first published in a lit journal in 2001, before making its way to Oblivion, a collection of short stories by Wallace.

The Pale King (2011)

Boredom forms the central conceit of The Pale King. Where Infinite Jest has a sense of manic energy to it—its maximalist prose and grand themes of entertainment spreading outward—everything here feels stiller. It’s inward-gazing. At around 500 pages, this is still a mammoth read; Wallace may be guilty of many things, brevity or economy of space isn’t one of them. To note: The Pale King is an unfinished novel; Wallace died by suicide while working on this, “the long thing”, as he referred to it, leaving behind meticulous notes and materials for his editor to assemble. Thus, this reads like a fractured, disjointed narrative, with incomplete threads and forays into themes that aren’t neatly tied up.

The story is, nominally, about a group of IRS (American tax service) co-workers, presented within a heightened reality that Wallace found great joy in creating. Take for instance a character named Drinion: he’s able to reach unreal levels of concentration, to the point where he literally, physically starts to levitate. A postmodernist metafictional tic, too, is a persistent thread: we meet a character named… David Wallace. One of the standout sections is a novella inside the novel, about a “wastoid” named Chris Fogle experiencing a spiritual awakening in an accounting class. The book is a fascinating, richly rewarding read; the loose ends, if anything, amplify the experience. A quick one-sentence teaser:

I was aware of how every detail in the classroom appeared very vivid and distinct, as though painstakingly drawn and shaded, and yet also of being completely focused on the substitute Jesuit, who was saying all this very dramatic or even romantic stuff without any of the usual trappings or flourishes of drama, standing now quite still with his hands again behind his back (I knew the hands weren’t clasped–I could somehow tell that he was more like holding the right wrist with the left hand) and his face’s planes unshadowed in the white light.

Brief Interviews with Hideous Men (1999)

Another short story collection, the centrepiece of which is a series of four stories that share their title with the name of the book. They’re transcripts from conversations (with an unheard interviewer) where all manner of terrible men expose their psyche to the world. Sickos, criminals, perverts, manipulators. Wallace, in these stories, dives deep into the inner machinations of masculinity and desire. These stories in particular have taken on a different hue in light of Wallace’s abusive behaviour with author Mary Karr emerging in the years after his death.

John Krasinski—perpetually bemused on The Office (US)—even made a film starring himself early in his career, inspired by the book.

‘Good People’ (2007)

Lane Dean, Jr. and his pregnant girlfriend, in this short story that would eventually feature in The Pale King, are debating their futures together. Their hopes and dreams and aspirations. He’s 19; she’s 20. They’re wondering whether to keep the pregnancy or abort it. They’re pensive, worried, anxious. Are they good people?

One thing Lane Dean did was reassure her again that he’d go with her and be there with her. It was one of the few safe or decent things he could really say. The second time he said it again now she shook her head and laughed in an unhappy way that was more just air out her nose. Her real laugh was different. Where he’d be was the waiting room, she said. That he’d be thinking about her and feeling bad for her, she knew, but he couldn’t be in there with her. This was so obviously true that he felt like a ninny that he’d kept on about it and now knew what she had thought every time he went and said it—it hadn’t brought her comfort or eased the burden at all. The worse he felt, the stiller he sat.

NONFICTION

‘Roger Federer as Religious Experience’ (New York Times, 2006)

Tennis as a theme appeared consistently through Wallace’s writing, in both his fiction and nonfiction—he played the sport at a pretty high level, and wrote about it extensively, obsessively. This New York Times piece about Roger Federer, where Wallace treats the joy of watching him play as an elevated—almost transcendental—experience, is an epitome of sports writing. As this piece in The Guardian declares, he was the “best writer on the game ever”.

‘Consider the Lobster’ (Consider the Lobster and Other Essays, 2005)

Arguably his most famous nonfiction essay: Wallace goes to a lobster festival in Maine to write about it for a culinary magazine and, in typically abstruse fashion, spends thousands upon thousands of words ruminating on the ethics of boiling a lobster alive for the enhanced pleasure that the consumer might derive.

So then here is a question that’s all but unavoidable at the World’s Largest Lobster Cooker, and may arise in kitchens across the US: Is it all right to boil a sentient creature alive just for our gustatory pleasure? A related set of concerns: Is the previous question irksomely PC or sentimental? What does “all right” even mean in this context? Is the whole thing just a matter of personal choice?

He attacks the argument with barely contained fury, drawing from his sharp understanding of philosophy (he studied philosophy and mathematics), linguistics, pop culture, and, indeed, neuroscience technicalities to explain which animals feel how much pain. It’s a dizzying ride, delivered with a surgical precision as Wallace—for all his detours and stylistically deliberate digressions—never loses sight of this fundamental act of cruelty.

‘Tense Perfect’ (Harper’s Magazine, 2001)

Language, Wallace argues, is political. While freakishly proficient across multiple disciplines, linguistics remained a personal obsession for Wallace. He would routinely break into punctuation-free sentences running into hundreds of impossible, 10-dollar words to express himself, and his work—as widely acknowledged—pushes boundaries in style and form. He was a massive nerd about this stuff; ‘Tense Perfect’ stands testament to that.

In this essay (which was later expanded), he questions linguistic prescriptivism with authority, flair, and wit—diving not just into semantics, usage, and grammar, but also the politics of language. Is it governed by a fixed set of rules? Or does it have a sense of fluidity and adaptability to it that is determined by prevailing norms and tugs-of-war over power. And he gave us the timeless acronym SNOOT—Syntax Nudnik Of Our Time—for that insufferable category of people clinging on to prescriptive norms in writing and expression.

This is Water: Some Thoughts, Delivered on a Significant Occasion, about Living a Compassionate Life (2009)

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?”

This essay was originally a commencement speech he gave at Kenyon College in 2005. In it, he talks about growing up, about empathy, about loneliness, about life. As Wallace aged out of his early, fetishistic postmodernist embrace of irony and satire, his words took on a philosophical bent as he reckoned with ideas of sincerity, with empathy, with kindness in his interviews. Some of that comes across in this very powerful speech that was first printed as an essay, before being converted into a book.

‘Big, Red Son’ (Consider the Lobster and Other Essays, 2005)

An exhilarating piece full of laugh-out-loud moments and a piercing grasp of entertainment and consumerism: here, he goes to the AVN awards—the porn awards—in 1998, and comes back with an astounding critique of the adult video industry. Morality, cultural decay, arrogance and conceit, mystifying details about the inner workings of this world. It’s a thrilling read from the first word to the last, as Wallace engages in a withering dissection of the industry, with not a small degree of sermonising and hand-wringing about the world.

*****

Akhil Sood is the Editor of Advisory.

souk picks

souk picks